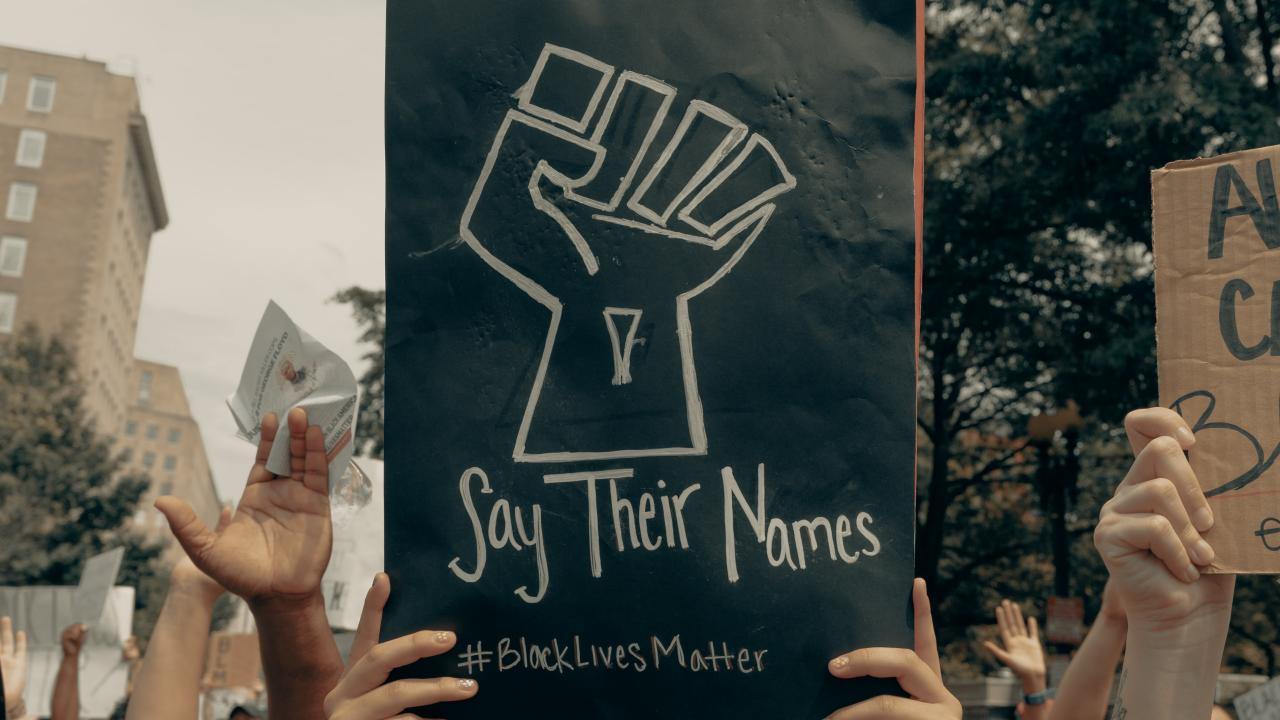

Almost six years ago, police officer Darren Wilson shot and killed eighteen-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Witnesses later testified that Brown was shot as he held his hands in the air and pleaded, “Don’t shoot.” Brown’s death sparked a monthslong uprising against police violence, during which protestors originated the chant still heard today: “Hands up, don’t shoot.” We sat down with two veterans of Ferguson — Tory Russell and Jeff Ordower — to talk about the promises and challenges of the uprisings, what it takes to sustain momentum in the streets, and what organizers today can learn from Ferguson. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Tell me about your political background and how you got involved in the movement.

Tory Russell: I guess my political background is, I was raised political. My family comes from an NAACP civil rights background. My cousin is Jesse Hill, who is very known in Atlanta. Has streets named after him, very instrumental in funding some things in the civil rights movement. My father participated in marches and tried to desegregate workers rights in the South, in Alabama, Mississippi. I grew up around the icons in St. Louis. The Zaki Barutis, the Anthony Shahids, the Jamala Rogers, the Percy Greens. My personal favorite, Ivory Perry, who is most famous here for chaining himself to the Arch. Direct actions where they painted the floor, him and Percy Green, they painted the bank floor in honey, which they call the stickiest protest in the history of the world. I grew up around those people and having that Black political dialogue. I don't think I was really active before. I would call myself a protest body. I came, I was, "Hey, it's wrong." Mike Brown happened, and since day one, I wanted to be more of an organizer than an activist or demonstrator.

Why did you want to be more of an organizer?

TR: Wanted to see more of a change. After seeing Trayvon not get justice, I went to a rally. It was a spontaneous rally. It was held in Tower Grove Park. People were talking. After that, it was really nothing. It wasn't in my community, I live in Northside, I stay in the hood. Tower Grove is a much nicer area than where I live. They were talking about issues that affect me, but it wasn't in my community. When Trayvon didn't get justice, I cried. I'm not going to lie to you. I have a son, he had to be three or four years old, and I questioned in my mind, "If I can't protect my kids and my family, then what am I really doing? Why am I even having children?" When Mike Brown happened, the vow of a lot of people across the country was, "If the Trayvon Martin situation happened to somebody here in my city, I would do blank." I wanted to hold up my end of that social contract.

Jeff Ordower: Like Tory, I was raised right. I was actually thinking about this because my mom is writing a chapter in a book about ’60s and ’70s feminism in St. Louis. That's my origins. And then I did a bunch of queer stuff in college. We didn’t use the term intersectional, but there was an intersectional campus left, where there were folks that were doing Central American solidarity — this was late ’80s, early ’90s, when there was hope for a left, or it was one of the iterations of hope for the left, with the Sandinista and whatnot. There was a bunch of stuff happening on campus, and then friends of mine went from there into the labor movement, and I followed them. And that's how I wound up at ACORN, because it was adjacent to the labor movement. That’s how I got into being a professional organizer.

You were both deeply involved in the Ferguson uprisings. Can you talk about that moment?

TR: Looking back on it, some days it feels like yesterday, sometimes it feels like it was a lifetime ago. I can remember, before the coalitions were built, meeting in the SEIU building, seeing Jeff, meeting Montague [Simmons]. It was funny to go from protesting, then they invited me to the room. Then, I'm in the room, and I meet somebody like Phil Agnew of the Dream Defenders, who occupied the Capitol Building. I felt like I was where I was supposed to be, really. I felt like I was in the right place at the right time. Being around other people like that, people around direct action, people who will talk about things strategically — and radically.

JO: What were you thinking? Were you like, "What the fuck is this?" Or were you —

TR: What the fuck is this. I became the new member of the Avengers. I saw Iron Man. I was like, "Okay. Some shit. I don't know how they found me out there. I'm in the right place at the right time. We having the right conversations." You know, Jeff, I've been around the country, around the world, having conversations. It's not too many places you can have real deep political conversations about real change. Really changing systems. That's rare. For me, I went to the room, I see Mama Jamala [Jamala Rodgers], I see a Montague with the Black Power fist, I see this radical Jew over here, I see these young people with crazy hair, that kind of room. I'm like, "Oh, shit. This is the shit I've always wanted to be in. It's time to go up. We might actually get free this time."

JO: What do you think we did well in moving in that direction, and where did we fall short?

TR: I think the best strategic thing was the small room because we could control the small room. Once it became an ACLU Don't Shoot Coalition room…. I get the coalition building part, but there are aspects of white supremacy that are going to show up. Once it became so big, it became a jostling of respectability politics, the strategy can't be so direct. Really, it became a money situation. The people who are outside [in the streets] can't get up at nine o'clock in the morning and have a meeting because they were outside until four or five o'clock in the morning. Those are the things.

JO: There were a series of background organizing pieces. There was what was happening in the streets, and then there were folks who were trying to undergird it. Really a handful of people, Tory and Tef Poe, who bridged both those worlds. A lot of people didn't, and [some] folks didn't even know there were different worlds.

There was a tiny steering committee that met every single day for a few months. That was Mama Jamala — Jamala Rogers, who had just left, one of the founders of the Organization for Black Struggle, who is back as the ED of OBS; Montague Simmons, who was the head of Organization for Black Struggle; me; and John Chasnoff, who had been a longtime white police reformer, who convened this thing called CAPCR, which was the Coalition Against Police Crimes and Repression.

Then there was a 10 AM meeting that was a little bit larger for folks who were doing jail support and other things. Then, some lawyers — the head of Veterans for Peace, Michael McPherson, who is an African-American guy, and Denise Lieberman, who is a white lawyer for the Advancement Project — convened this larger thing called the Don't Shoot Coalition. The political utility of that was to have the voice of the non-profit organizations not condemn the nighttime protestors — because we were headed that way. Michael and Denise made that decision to keep message discipline, so you didn't have groups being like, "There's good protests and bad protests." There were daytime protests, and there were nighttime protests. The nighttime protests were the messy ones that the power structure didn't want. Obviously, the racial divisions among the protests were much bigger, too. That was why there was this Don't Shoot Coalition.

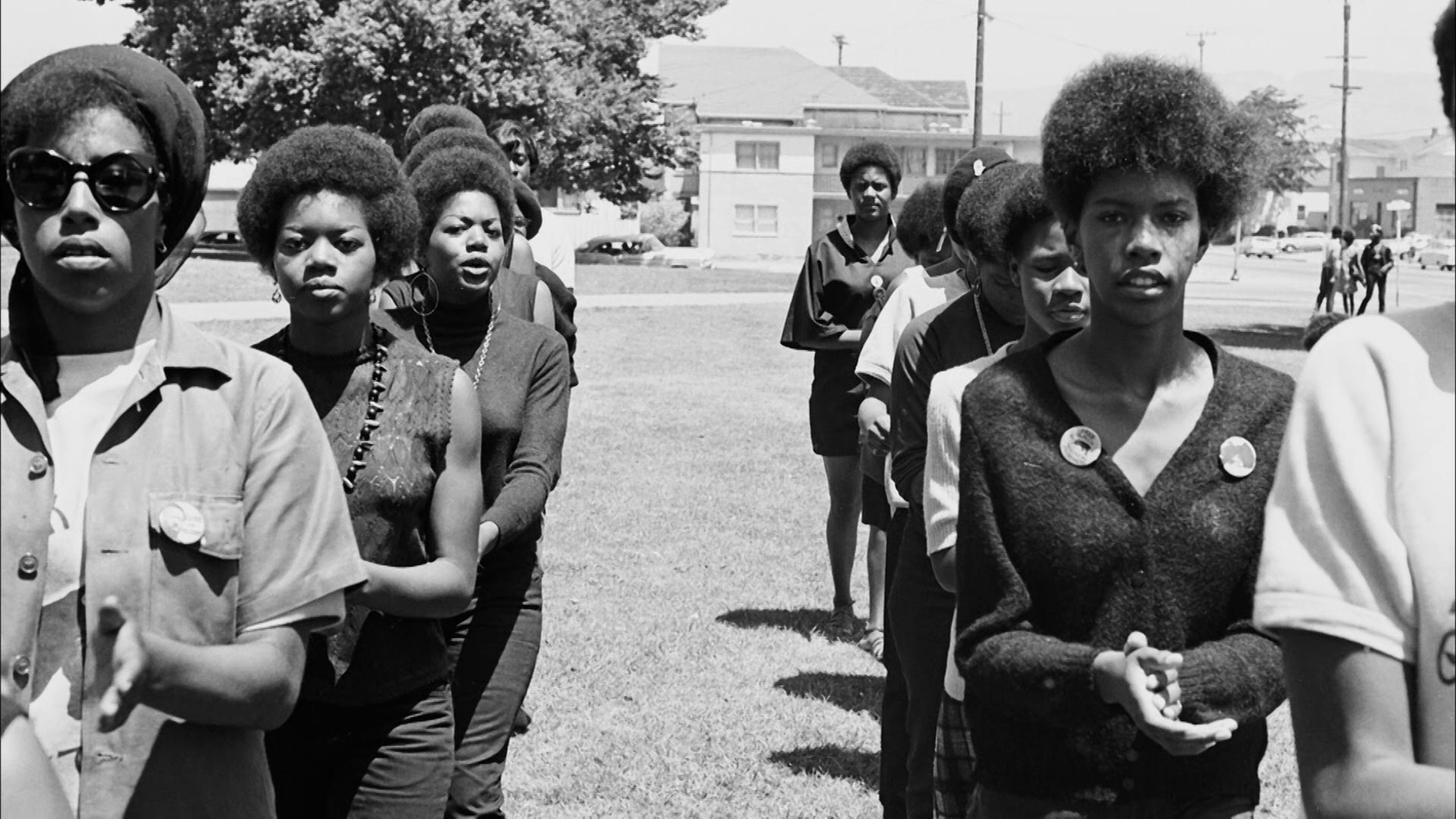

To your point, Tory, there was no [existing] Black political infrastructure. The state destroyed radical Black organizing in the ’70s and ’80s. The people who were running organizations, who are the paid organizers, including me, were a bunch of white folks. There isn't a Black middle class in the St. Louis region in the way there is in Atlanta or in other places, too. If you're hiring people who are middle class, you're going to hire predominately white folks, and I was as guilty as anyone else of that bias.

During the Ferguson uprisings, did more Black folks come up and lead the organizing efforts alongside the people who were already in organizations?

TR: Yes, but out of the Don't Shoot Coalition, and not a lot of people out of grassroots. What it created was a conflict on some points, and it became a race struggle, and then a race struggle with a class struggle. That was Ferguson. Yes, Ferguson is 68 percent Black, but 20 percent of the businesses are Black owned. You see what I'm saying? They had one Black person on the City Council before we protested.

I remember when we organized Ferguson. In October, me, Tef Poe, and Ashley [Yates] were put on a flight to New York to do Democracy Now!, Huff Post, Marc Lamont Hill, we doing the rounds. Me, Tef, and Ashley had $60 amongst three people in New York. We had that for about a day. We on TV, so the assumption is, Tory and Tef and Ashley got money. We're broke as fuck. We're starving. We couldn't find a hotel. I paid my rent through one check two days before I was going to get evicted. That was my first check. August 9th, Mike Brown got killed. We protested. I didn't get no money in August. I got no money in September. October, I got money, and I paid three months of rent. I didn't get any more money until February. I was broke. I was told that no one was going to pay me. They gave me one check. I didn't get the other check. I'm broke.

What happened when the uprisings died down in Ferguson? Were you able to build more grassroots organizing in the city?

TR: We were because we created our own organization. We were not treated as part of the coalition, and then we were removed from the coalition. Then, what happens is, they go find anybody. It's just like national. I left Black Lives Matter in 2016, I left working with the Don't Shoot Coalition in 2015, and basically was replaced by any protestor that you can find. What it looks like is, Ferguson is growing, but in actuality that part was co-opted intentionally, because the Don't Shoot Coalition members, in my opinion, needed outside people at the table to inform them of what's going on, and to have validity.

JO: There was no way to have good conversations about money. I will own the decisions I made around money, as one of the few people in the room that had access to resources. I think a few things on money. The first thing is, this was my takeaway from watching the Katrina organizing while I was in ACORN. There were three separate radical hurricane relief funds. There was ACORN, there was the People's Hurricane Relief Fund, there was Common Ground. They didn't speak to each other, and it broke down around money. Neoliberalism won in New Orleans. My takeaway from that is, we needed to keep the money combined. We created this slush fund, essentially. That was the thing that moved tons and tons of cash to the protestors for food.

A bunch of people, including Dream Defenders and Occupy Sandy, were like, "What you have to do is support the building of new organizations." To your question of what happened. We encouraged, and I don't know if this is right or wrong, a whole bunch of groups to form. Freedom Fighters and Millennial Activists United and Tribe X and many more And anyone could give money to The Center for New Ideas, put in the tagline, "This money is for them." And then we would just give them that money in whatever form they wanted. Cash, check, whatever. That was the money.

And then, simultaneously, we (Missourians Organizing for Reform and Empowerment) hired six people in August, which was probably a bad idea. But, we were like, "It's going to move from disruption to organizing." A whole crew of frontliners worked for us for a couple of weeks, and they actually quit in a very principled way. They were like, "Screw this, we're not ready to organize. We're going to stay in the streets."

I think that was a set of rational decisions around money, but that didn't make it any less complicated. There were still people who had put it all on the line, who weren't getting a dime, and then people who had a day job that was supporting them. I was still getting a paycheck from MORE. The Organization for Black Struggle was the group that was the most known, for a variety of the right reasons, including that they'd been doing the work for 30 something years and they had never had any funding. They went from an unfunded group, to a group that had a pretty decent-sized budget that year.

TR: Organization for Black Struggle been around for 30 something years. I know Percy Green, I know Mama Jamala, I never heard of Organization for Black Struggle before August 9th, 2014. In the Black community, they didn't exist, and I'm pro-Black. I grew up with Malcolm X on my wall, marching, protesting. I was expelled from a suburb school, all white school, because I started basically a race riot in 8th grade. I've been this kind of person all my life, and I didn't know these organizations. They show up, and after we do the grunt work, talking to Harry Belafonte, talking to Danny Glover, talking to Jesse Williams, talking to these people, OBS is the beneficiary. They get the $88,000 from Color of Change. They get the $40,000 from the Dream Defenders selling T-shirts, thinking it's coming to us. They get the 100 grand from the Advancement Project. Me, Tef, and Ashley Yates, and Bassem [Masri], and T-Dubb, we probably received $10,000 in five months. We are starving. We're sleeping on each other's couches, sharing meals like it's the Panthers in ’71, and we in a Panther House. I have two kids, by the way. It tears up everything. Tef has no girlfriend no more. My girlfriend leaves. It's too much. Too much FBI. One day I got home, Charles, the dude from the FBI, was sitting at my house. Nobody wants to be in a relationship with that. Nobody wants they kids around that, and you not paying no bills. And you hungry. And we at a food pantry. The struggle didn't take care of the people who were struggling. But Bukky is okay, because she's an adjunct professor at SLU. Montague's okay because he's a more acceptable black person. He has a college degree; I don't. That became the conflict, and then how do you sustain it? And then, on the outside, if I'm the most acceptable that you can have in the room, then what is the lost voices?

JO: Money is super toxic, and also the way folks are able to position for it matters, in terms of who gets credit for the work. I don't know what you do about that.

TR: To me, money is like sex. I don't really care who you have sex with, but it might produce a baby, and you're going to have to deal with it, forever. Yes, you give money to groups, those are your children at this point. If you leave people poor for so long, and all you see is cameras, then they get nervous.

JO: You talk to your average person who showed up, your 19 year old who showed up in Ferguson, they were very clear the whole damn system is guilty as hell, and they had an analysis of that. I think we were unable to figure out what the right organization was to bring those people into, to try to tear down the system and get to something else. What's your take on this wave [in Minneapolis] for people [on the streets] who you're talking to about it?

TR: The last six weeks since George Floyd [was killed], I've been everywhere. Because I want to understand what's going on. I want to impart the wisdom that I learned. So what happens is, you have the traditionals, then you have the up and coming, then you get the burst of new energy. Then there are some other people that are outside that won't never receive what the ACLU is talking about. They're not going to get access to the Minnesota Freedom Fund. They're not a part of the Black Visions things. There's people outside like a brother named Larry in Minneapolis that we hooked up with. He like me. He an organizer. He don't know it, right? It was a Somali sister on the north side, I believe. I mean, on the south side of Minneapolis. She’s an organizer, don't know it, right? There's others that need that support or that training, and that's been my question. How do you support them other than direct resources?

Then how do you educate them politically so that they don't get absorbed into what I think is like the fuck shit. I don't know if we need the talented tenth Negroes who always come in and be the think tank for the movement, for Black people. But time and time again, that's what happens. So why are we continuously in movements in the U.S., not putting stock in organic intellectualism as much as we are putting into academia and scholarship. So when people say the whole damn system is guilty as hell, the political analysis from the people in Ferguson was like, "The police fucked up, the housing fucked up. My tooth hurt and ain't no health care in this motherfucker." Right? That is a deep and honest political analysis. What needs to happen? They will say, "Shit, I need a motherfucking hospital down here." That is also a solution.

If you don't have that principle to not compromise on the demands, then why create the demands in the first place? Because you're just putting yourself in a place to take money and a platform and a place to speak away from the people who need to learn how to speak for themselves. You could just teach them the language, not become their spokesperson. You keep them oppressed by always jumping in and doing it, in my humble opinion.

JO: Almost no one (white folks) was willing to put any political or social capital on the line in the Ferguson movement. Anyone who had any kind of class privilege wasn't willing to make any sacrifices. So whether you were a lawyer and you were friends with the municipal court judges, you weren't willing to transform that system or even to call out your friends in the legal community for running this corrupt, fucked up municipal court system. If you were a community organization, maybe you pulled your money from the head of the police union. Maybe you didn't because he was a pro-Medicaid expansion Democrat, and so you kept working for him secretly behind the scenes. Or you weren't willing to tell off funders, or you weren't willing to go to the power structure. No one really put much on the line, which is why the material conditions for Black folks in the St. Louis region have not changed or, in fact, have worsened. I think about that around George Floyd too. There's a whole bunch of pieces of social capital that predominantly white folks are unwilling to risk to bring about change.

But the militancy with which folks stayed in the streets [in Ferguson] for months and months and months is, I think, unprecedented. What do you think made that happen, Tory? That really does not have historical precedent in the U.S.

TR: A belief that you could win. I think for a lot of people, to see power, to peel back the curtain in the Wizard of Oz, to see how weak this shit is, to see that you actually stronger than the thing that holds you back — drives you to keep going. We don't walk on the sidewalk because that shit is just weak sauce because we have now understood we don't need a permit, we just do the shit, and that's just what Ferguson is. Other places I've been to, they was like, "Well, we calling the City to get a permit." And I was like, "You all still doing that shit?" You still wasting time, you paying for it, you asking? We set up whole stages wherever the fuck we wanted. Like a stage will be there Saturday. We're going to march with a couple of hundred people, a thousand people. Once you taste that, it's over.

I tell people all the time, I have been in three places in the world where I've tasted freedom. I have been in Ferguson and had freedom wherein the police literally could do nothing. I've taken cars off tow trucks. I've stopped people from getting evicted. Right? I have seen people eat food that they didn't pay for. Okay? Out of rich corporations. We ate good as fuck. Right? Because we deserve it. I've seen that level of freedom sitting in the street. I've seen it in MST in Brazil. I've seen that in Zambia, in Africa. Once you taste freedom, it's very hard not to have a hankering for freedom for the rest of your fucking life.

I feel like [in Ferguson], we created a big enough pot for people across the country to stick a spoon and get a taste of it. Now they're going home and trying to figure the recipe out at home. Once you get a taste of it, you sustain yourself off of the belief that you can make that personal recipe or get that taste again. That's the only reason why I kept going. Everybody know you will find me at a protest somewhere sitting down as if I'm not at a protest. I was at the Mayor's front yard, laid the fuck up on her front stoop, on live, face mask down, people rolling blunts, drinking on the Mayor's front yard. I'm like, yep. That's freedom. Sex workers walking through the grass, black trans women. We free as fuck out here. I don't know what to tell you. I don't know. You might want to do some of that where you at. I don't know. It's probably like Occupy for Jeff, or like Seattle, they have an autonomous zone. Like that shit, it do something to your spirit. How do you sign back up to be oppressed? I don't know.

JO: That totally resonates. Amen to that. So, you're saying you see organizing as this kind of clash or pressure, like the way things change is we're constantly in the street. There's constant disruption, so that's what wins. Then there's this whole power structure, call it what you will, including the constraints we put on ourselves, about moving into policy and strategic campaigns and policy papers, which doesn't actually create the change, or is a slower track.

TR: I think it's a slower track. I think that the protest or the direct action creates the space to create the alternative.

JO: I completely agree with you, and I think it's a question of whether you're tearing down the system or trying to get policy wins within the system. So, from Ferguson, the freedom that folks felt so they stayed in the streets for months longer than most other movements — why do you think that stopped? And how do we think about that for movements moving forward? How do we maximize the number of folks who are disrupting the streets?

TR: Sometimes, it's the role of people like me. At this point, I'm the O.G., I have to teach the young Elijahs and other people now about being both hands. You gotta be the revision people, you gotta be the direct action people and the think tank people almost simultaneously, or your movement's going to get co-opted.

How do you think about the times in between moments of mass direct action? What's the work to do in that time?

TR: Deep, hard, long, strenuous political education. And implementing the things that you know need to happen now. It's time to go old school. It's like, we have to physically get in front of each other. Politicize, educate, have these debates. If I say Gramsci at a protest now, people will look at me crazy. They be like, "What are you talking about?" You know what I'm saying? But until we get into a space where we can talk about EFF [Economic Freedom Fighters] or Patrice Lumumba and those things, you won't have a deep political conversation. To me, it's limiting the ability to dream of what freedom is. We need Black space. We need Native space. I am very intentional about being a part of other movements and learning from them. I was in Standing Rock. Black people was like, "That's not your struggle. Why the fuck are you there?" I'm like, "A struggle for land is a land struggle, period." Now, we're trying to build a freedom school on Native land. So we can have our own MST kind of spot. Black people need that too. Black people need their own specific Black spaces to learn, educate, be more radical. If we create those things, then we can have a sustained Black radical thought.

JO: Right now, I think, besides maybe the Twin Cities and New York, St. Louis is in motion more than anyone else. They canceled all the high school football games one weekend in 2017 because the disruptions were so intense. How are you feeling optimism versus pessimism around that? Do you agree with what I said: that material conditions for Black folks in the region haven't improved?

TR: I mean, I've got to be optimistic because it's still going outside. I'm not a suicide bomber. So I'm not that pessimistic. I believe that we could change these things, like you said. I got pushback because I'm not starting nothing small. So you say, Close the Workhouse; I say close America. I say close all the jails. Because I know they going to close the workhouse as a concession. I'm saying that we should be getting billions of dollars from these corporations to materially change the lives of the people in St. Louis. Free housing, affordable healthcare, those things. Once you see that Wash U or Bayer or Anheuser-Busch has millions upon millions of dollars that's sitting there, and they're supposed to be using it for the community, then you can start educating people on why we deserve it, and how we can use it to change not just one life or a 100 lives or 1,000 lives, but all the lives of Black people in St. Louis.

JO: So you're saying, in this moment, the demands were too small. The demand was defund the police nationally; police departments are getting defunded. If the demand had been abolition, we'd be moving closer to that.

TR: We nickel and diming ourselves when we could be getting dollars. To me, it's like, to defund the police is to allow the police to abuse you at the same rates with less funding. Because all they going to do is keep all the bullies on the payroll. Because the contract not going to change, right? The people who in power not going to change. So the Mayor's going to hire a police commissioner or a public safety director. They're going to hire a police chief that's a bully, and they're going to have nothing but bullies. So when you do encounter the police, it's going to be really fucked. They're going to concentrate in the “problem areas,” which is where I'm at. So there's going to be less police for white folk, which is already what's going on, more concentrated efforts on drugs. I don't have a boat or a plane, and so they're going to beat me up and kill me in a more concentrated effort, and they're going to say, "Well, we defunded the police. You still have crime. Maybe we should relook at defunding the police, maybe getting a little bit more police, but more strategic." Then it's going to be an uptick back to what they think is an adequate amount of police. They always ask for more money and more police. So if you cut it from 1,000 to 500, in four years it might be 750.

What's giving you both hope right now?

TR: It took five years, really, but people are mobilizing across the country when something happens to somebody else. That's first. George Floyd is not in St. Louis, but people are outside as if someone just got shot. So I'm hopeful in that aspect of it. I am hopeful that it's more young people, movement babies. It's kids that were in elementary school or middle school when Jena 6 happened, Hurricane Katrina happened, when Mike Brown and Trayvon Martin happened. Now they on the streets trying to organize. That gives me hope because I know I would burn out. Some of my people have sold out, burned out, left, cried, given up. So with more young people, if we have an infrastructure to educate them and motivate them and refine their tools, there's nothing that's going to stop us.

JO: Hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets in a pandemic. Shit. People are at the front lines, to Tory’s point. Folks took Ferguson and took it up a notch. I'm so inspired by what folks are willing to do. The other thing I'm optimistic about is that I think we're much better within the movement more broadly of being self aware about who we are and what our lane is than we have been. So I think folks are introspective, don't believe that they personally or that their organizations have all the answers. Then, as a white person, I just think this sea change on race, in terms of, it's not the U.S.'s original sin, colonization is, but it's a huge part of our DNA — and if, in fact, millions of white folks are willing to engage with that sin and that history, I think we can actually break through to a much larger look at the political economy of this country and how we're going to change things.

Become a Sustaining Donor to The Forge!

The Forge is built by and for organizers. Though we’ve raised a bit of startup money to build the site, this publication and community will be only as strong as we, together, make it.

Please click below to become a sustainer. When we have some cool swag, you’ll be first in line!

DonateRelated Articles

How to Build a New World, Locally

Ferguson, Palestine and “The Most Important Election of Our Lifetime”

Will the Revolution Be Funded?

From the Traumas of America to the Shores of Africa: A Journey of Self-Healing

Get the latest articles sent to your inbox