The voting age in the United States has been 18 since 1971, but over the past decade, cadres of youth around the country have been working to expand voting rights to 16 and 17 year olds. In 2020, Oakland, CA, became the latest city to take that fight to the ballot. The ballot initiative was the result of months of youth-led organizing by Oakland Kids First (OKF) and partner organizations. In this piece, Sonja Kaleva, a member of OKF’s Youth Organizing Council, talks with OKF executive director Lukas Brekke-Miesner about how the Oakland Youth Vote campaign came to be and what lessons they learned along the way.

Setting the Table

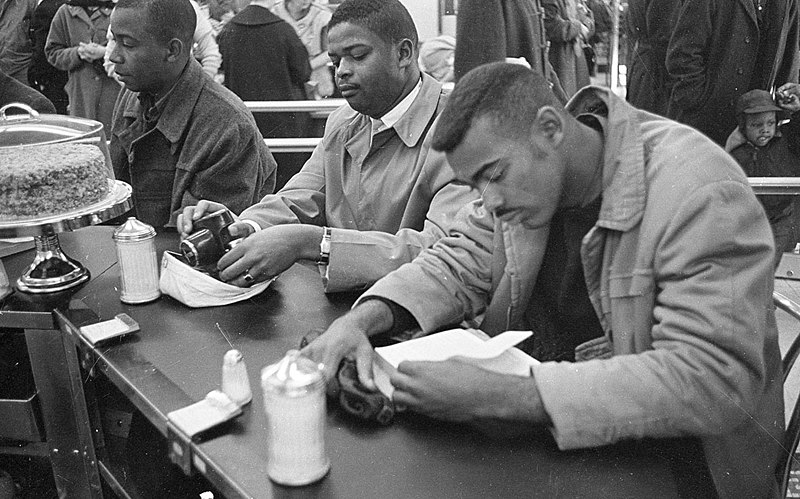

Sonja Kaleva (SK): “We want to be at the table, not on the menu!” has become a common refrain among Oakland student organizers over the past couple of years. It originated as a response to the Oakland Unified School District’s (OUSD) annual budget cuts that were decimating student support programs. Student organizers would regularly show up to board meetings to pressure board members to enact our demands, but we were consistently ignored. There were small battles won along the way, but we were losing the war for our education.

Lukas Brekke-Miesner (LBM): What became abundantly clear was that while youth had access to meet with some school board members and share their demands at public meetings, they had little recourse when they were ignored or tokenized. This came into sharper focus after a tumultuous 2019 in which the Board of Education used the teacher union’s new contract as an excuse to cut even more student services, such as restorative justice, foster care case managers, and a support program for AAPI youth. Despite powerful testimony from many of the 500 youth assembled at the school board meeting the morning after the teachers’ strike ended, the school board proceeded to take a hacksaw to programs that support vulnerable students. It was clear then that even large and compelling mobilizations weren’t going to reorient OUSD’s priorities toward students.

Understanding Power

LBM: While youth have long used advocacy to convince adult decision-makers to “do the right thing,” they generally can’t force issues because they don’t possess social power. As Steve Jenkins, a labor lawyer and community organizer, writes in Organizing, Advocacy & Member Power, “Unlike advocacy, which is based on a group’s ability to persuade elite institutions to take action, social power must be based in some capacity by the group itself to coerce the decision-maker to make the changes they seek.” What Oakland students needed was a lever to control the conditions of the education system. If the game was rigged against them, then the rules had to change. So that’s what they set out to do.

Vetting Our Campaign

SK: I had not yet joined Oakland Kids First’s Youth Organizing Council when the controversial school board meeting went down, but many of my peers were outraged. Student leaders with OKF and All City Council Student Union (ACC) took the summer of 2019 to research what steps we could take to gain power within OUSD. My peers discovered that there was an emerging movement to enfranchise 16 and 17 year olds in local elections; the movement had met some success in a few towns in Maryland and even in neighboring Berkeley, where youth successfully organized to pass a 2016 measure to allow 16 and 17 year olds to vote in school board elections. (Despite continued advocacy, the measure has yet to be implemented.)

LBM: Organizing for voting rights for young people felt like a compelling way to gain a foothold in district decision-making and give students power if school board members continued to vote against their interests. The strategy came with an added bonus: it would engage voters before the age of 18, thereby creating an onramp for democratic participation in future elections and increasing turnout among 18-34 year olds.

Building a Coalition

SK: At ACC’s annual autumn retreat with student leaders and adult allies from various organizations, OKF and ACC students pitched a campaign that would enfranchise 16 and 17 year olds in school board elections. After discussion, youth voted to adopt this campaign and asked our adult allies to help us explore the issue. Our organizations focus on youth leadership and youth organizing, but we also rely on adult partnership and intergenerational approaches to help propel the work forward.

LBM: Most of the groups in the room had previously organized to pass policies at the school board level and fought for student budget priorities, but few of us had experience running a citywide electoral campaign. We knew there was precedent for this kind of campaign, but we still had to determine the feasibility of winning in Oakland, the capacity of our organizational staff and youth members to lead the campaign, and the timeline that made the most sense.

A game-changing campaign of this magnitude doesn’t happen without building a wide base of support and that starts with coalescing a strong team. Without the partnership and participation of Californians for Justice, Youth Together, AYPAL, Oakland Youth Advisory Commission, Power CA, the Justice for Oakland Students Coalition, and donors, this seed of an idea would never have sprouted the way it did.

Building formations are critical to vye for power but that doesn’t mean they come easy. The speed of a campaign requires the ability to make quick decisions — and membership-based organizations’ decision-making processes aren’t typically built for speed. There were instances when we had to rush a decision without sufficient deliberation and times where we stayed in process at the expense of expediency. One such example was the construction of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). As campaign leads, we drafted an MOU so we could have accountability with partner organizations, but our coalition partners pushed back on our draft in favor of a more collaborative agreement. This took a lot more time to develop, but without that inclusive process, the coalition could have splintered.

Another tough reality we had to navigate was that each group had varying levels of capacity, interest, expertise, and funding to throw down. Member orgs also experienced staff and student turnover and the pandemic pulled all of us into a triage level of service provision. This created unease and unpredictability that made certain legs of the campaign feel inequitable, but we also realized that evolving dynamics come with the territory.

SK: At the heart of this whole effort was students’ dream to win the right to vote. That required a lot of labor, but we needed to lean on each other because we’re all full-time students and many of us are new to organizing. Then the pandemic hit mid-campaign, preventing us from meeting in person and pulling many of us into child care roles, virtual learning, etc. Being in coalition with youth and adults from other groups allowed us to share the load of the campaign when things got hard.

Youth Development within Youth Organizing

LBM: Oakland Kids First subscribes to a key definition developed by the Funders Collaborative for Youth Organizing, which states, in part: “Youth organizing is the process of engaging young people in building power for systemic change while supporting their individual and collective development.” Building power is the ultimate goal, but developing solid young people who feel safe, heard, and powerful is also critical. That means that sometimes the clip of a campaign needs to slow down to ensure youth feel prepared to make strategy decisions or to prepare for a particularly important meeting. Students are the locomotive of the OYV campaign, but in the spirit of sound youth development, adult allies try to stay a step ahead, laying track by creating safe spaces, identifying learning objectives, developing curriculum, fundraising, and generally supporting student growth and success.

SK: I’ve thought of my time in OKF programs like being in a club because every Tuesday and Thursday we’d come together, sit in a circle, talk about trivial things, and then play a game before delving into campaign updates and whatever educational topic was planned for that day. All the adults are very kind and fun and you can always tell that they enjoy working with us and care about us. They support us and are invested in our growth. Those are the things that matter.

Navigating the Political Process

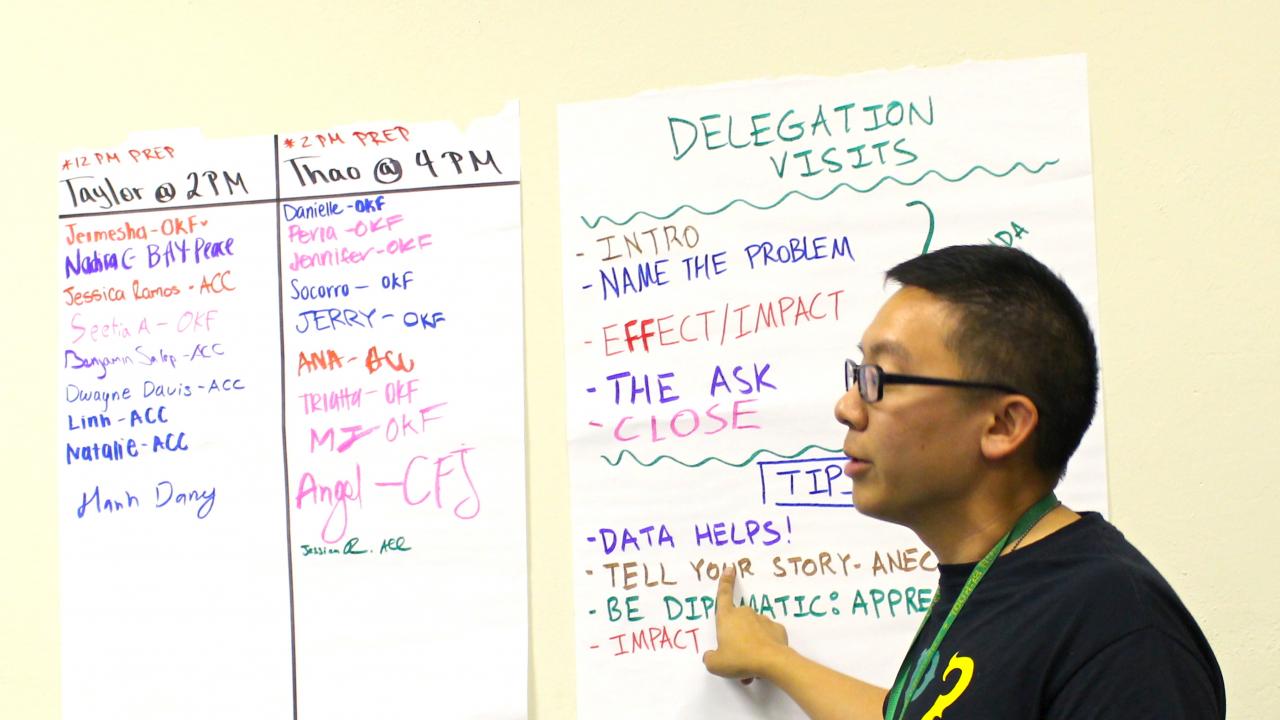

SK: In order to win 16 and 17 year olds the right to vote in school board elections, we needed to amend the city charter — and we couldn't do that without voter approval. To get our initiative on the ballot, we could either gather signatures from tens of thousands of Oakland voters or compel the City Council to place it on the ballot. We determined that working with the City Council would be a speedier process so OKF's Youth Organizing Council began to power map the City Council. The goal was to determine which issues they supported and opposed so we could develop pitches catered to their values and interests. After we had completed our power analysis, we joined youth leaders from partner organizations to meet with council members to see how supportive they were and try to convince them to put OYV on the ballot. The more we met with council members, the easier it got. This was a common theme in our work — the more we did, the easier it was to do it again.

LBM: Council President Rebecca Kaplan signed on as the author of the resolution, and after months of meetings, the youth organizers successfully garnered support from the majority of the council. Just when we were getting close to bringing the resolution to committee — the first step towards having council place the measure on the ballot — the COVID-19 pandemic hit and everything shut down.

Forcing the Issue

LBM: We feared that the ballot initiative would be dismissed as gratuitous in the throes of an unprecedented public health crisis, but youth were hugely impacted by schools shutting down. Furthermore, the pandemic had prompted national conversations about the future of public education with no input from youth. There is never a “good time” for the establishment to give up power, but this actually seemed like a critical moment for youth to pull a seat up to the table. So they kept pushing.

When council meetings resumed (virtually), some council members who had originally pledged their support began to waffle. Because the Brown Act prevented our council sponsor from reaching out to each council member to shore up their support, the OYV coalition had to circle back and get them to recommit. Things felt like they were on the right track until the night before the vote, when a council member decided they would introduce an amendment on the floor that could have jeopardized the OYV legislation. We were saved by an unlikely hero, an outgoing moderate who utilized a parliamentary maneuver to motion for a vote on our resolution before the other council member could introduce their amendment. It served as a reminder not to count out those we had disagreed with in the past. In the age of cancel culture, watching youth wrestle with the mantra no permanent enemies, no permanent friends was a transformative moment.

SK: Our persistence paid off, and the City Council unanimously voted to place OYV on the November 2020 ballot as Measure QQ!

LBM: We tried to celebrate, but screaming alone in our kitchens didn’t feel quite as joyful.

Leveraging Media & Securing Endorsements

SK: With Measure QQ now officially on the ballot, we needed to reach voters — during a pandemic — to get their support for QQ. One of our strategies for campaigning during a pandemic was to generate media coverage of our cause. We nominated student spokespeople to talk to the media about our campaign. My friend Ixchel Arista was one of five student spokespeople who talked to news outlets, community groups, and potential endorsers to generate interest in Measure QQ. Our efforts were covered by local news outlets as well as national ones like Teen Vogue and The Washington Post.

LBM: Endorsements are always critical to generate support, but this is especially true in elections with a deep ballot, when endorsements become a shorthand guide for voters. Student leaders and adult allies asked elected officials, community organizations, unions, and school principals to back Measure QQ and generated an impressive list of endorsers, including U.S. Congressperson Barbara Lee, the Oakland Education Association (Oakland’s teacher’s union), the ACLU of Northern California, and the League of Women Voters.

Educating Voters

LBM: Because we were running a campaign during a pandemic, we decided it wasn’t safe to have youth walk precincts to talk to voters in person. But with a limited budget, we couldn’t rely on a barrage of TV advertisements like many other campaigns. We needed to develop a strategy that would allow students to break through the noise and share their passion with voters in a cost-effective manner. Students filmed a short commercial that ran online, they generated social media content, and they distributed lawn and window signs to spread the word. But our most robust voter outreach tactic was calling voters and sharing why this was a critical measure worth supporting. We didn’t have the existing infrastructure to do phone banking on our own, so one of our allies, Power CA Action, provided the technology and training to conduct remote phone banking. A grant from Power CA Action allowed us to pay some phone bankers, and we recruited additional youth and adult volunteers to bolster our ranks.

SK: Phone banking gave me more anxiety than anything I had experienced thus far in my life. Talking to adult strangers who could have such a variety of opinions and beliefs, who might yell at us or call us names or even just not agree with us, was terrifying. The first time I phone banked, I spoke with someone who believed that teenagers should focus on being teenagers and not worry about things like voting. I told her why I was passionate about QQ, and she told me she would look into it because of what I had told her. The sense of victory I felt was overwhelming and so motivational. My personal stake in this cause was able to sway her stance. I wish that we could’ve phone banked together in person, but we made up for not being together by texting our group chat whenever we had a question or wanted to share a funny experience, vent about a rude person, or get support for our nerves.

Implementing Legislation

SK: As you may already know, we won the campaign. Oakland voters passed Measure QQ with over 67 percent of the vote! It was so relieving and gratifying to know that our hard work paid off.

LBM: From the very beginning, we understood that each phase would be more difficult than the last. Phase 1 was to get Measure QQ on the ballot, Phase 2 was to convince voters to pass it, and Phase 3 is to get it implemented. We’re currently trying to compel multiple layers of government to work with each other and community stakeholders to implement Measure QQ, but it’s a long and complicated process. We passed legislation, which is exciting, but we have to remember that it’s not a real win until material conditions change on the ground. And that requires more organizing!

Here are our main takeaways from this experience thus far:

-

Remember you’re organizing people. When organizing, don’t put the issue over the people – especially when working with youth. While systems change is critical, we are engaged in this work for the people. If our organizing is transactional and burns folks out, we are not being any more liberatory than the systems we’re fighting. It took a great deal of time to center youth development practices, skills acquisition, issue expertise, and collective decision-making in the heat of a campaign, but those things are all core to our vision of youth power. The policy change won’t mean anything by itself if there aren't powerful youth leaders to lead the next charge.

-

Fight for rather than against. When organizing, it’s often easier to generate momentum when you’re rallying against something, but this means that we’re often baited into fighting to hold onto crumbs rather than fighting for the pie. Sometimes those fights for survival are extremely necessary but, when possible, think about what would be game changing and fight for that.

-

Contend for power. We realized that a lot of what our organization had historically considered organizing might be better defined as advocacy. We were developing asks, piloting solutions, sharing testimony, and critiquing elected officials, but we often weren’t using those moments to build our base, improve organizing conditions, and raise our profile. This campaign was different: our voter outreach work drew attention to our cause, winning voting rights improved our organizing position, and we’re now constructing an education justice platform informed by the needs of thousands of marginalized Oakland youth. The platform will be used to pressure, evaluate, and vet existing and aspiring school board members.

-

Team work makes the dream work. Bringing groups together with different perspectives can help you craft a more thoughtful organizing strategy, distribute the workload, and strengthen your organizing ecosystem. But it can also be difficult if you aren’t building your shared work on a foundation of trust or if there is confusion regarding how much capacity each member organization has. We recommend establishing an MOU that delineates working agreements, responsibilities, and protocols for how decisions are made and how to address conflict when it arises.

-

Build on your win. We took time to celebrate our Measure QQ win, but we also know this electoral campaign is part of a larger fight. Measure QQ changes the rules, but we still need to ensure those in charge of our elections follow these new rules. The OYV coalition is currently conducting research to create an education justice platform and pressuring local and state officials to set up a voter system that allows 16 and 17 year olds to register and vote. Then, in the lead up to our first election with youth voters, we will do voter registration drives, issue education, and voter mobilization.

Conclusion

The OYV campaign isn’t just an effort to win voting rights; it’s an effort to secure power where youth historically haven’t had any. OUSD’s school board makes decisions every week that impact young people, but we have always been on the menu rather than at the table. The hope is to leverage every opportunity to shift the nexus of power toward students. We will keep fighting to center our needs and solutions in the interest of pushing OUSD toward it’s promise of being a rigorous, equitable, and anti-racist school district.

We won a campaign with a direct target, but the Three Faces of Power teach us that we still need to continue building durable long-term coalitions and win the battle of ideas. To that end, we will continue to forge powerful formations and be a resource for organizers in other cities, municipalities, and states who want to use Youth Vote to build youth power on a larger scale.