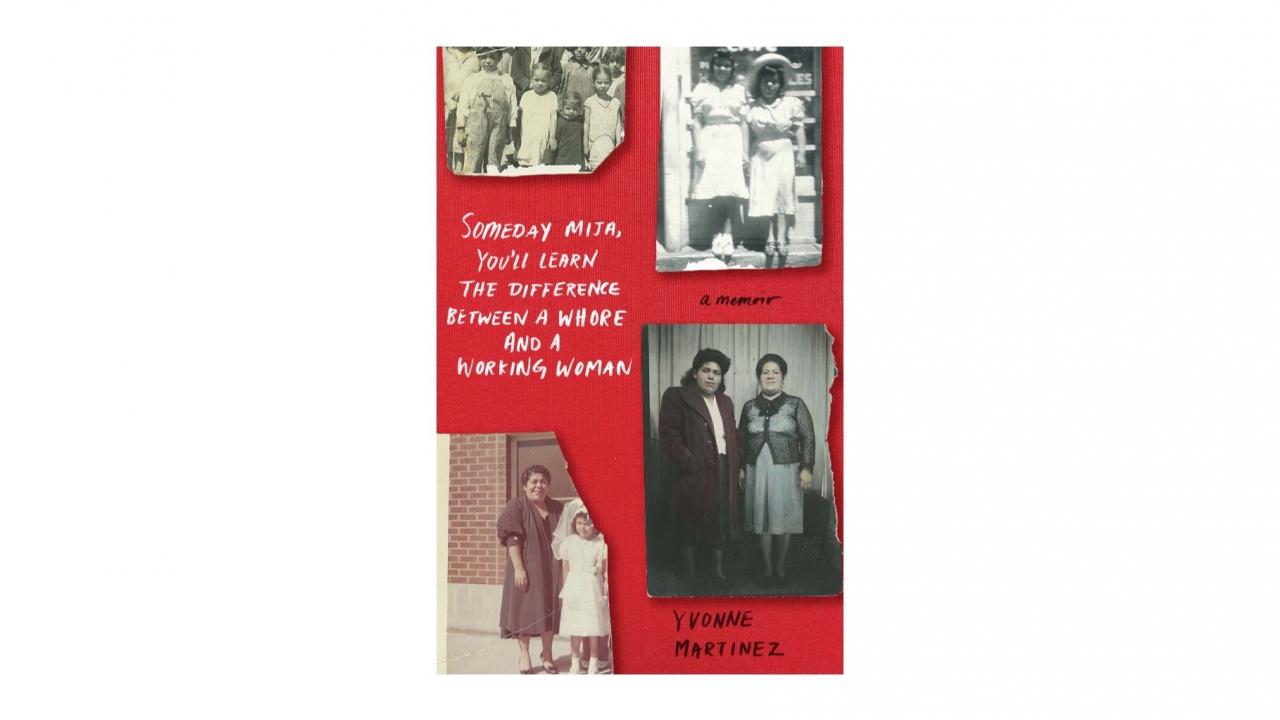

I was seven years old the day the call came. Salt Lake snow was so fat, it knocked on the door to see if we could play. “You’d better come and get Mary, she’s shut Frank’s down again.” Before Mother could send my stepfather to get Grandma Mary, a cab pulled up with her in it. She wore a black wool swing coat with a velvet collar and a big rhinestone button at the top. She pushed the snow off her coat as she took it off in front of the fireplace to reveal her work clothes, a well-cut black dress and heels. “We cost him more today than he’ll make in a week,” she said to Mother. “Get me a beer, will you Margaret?”

“Those bitches were just giving it away,” Grandma continued as she took a sip of her beer. “He tried to cut us out again, cabrón.” With no pimp, Grandma’s crew kept what they earned. They were being scabbed by women the tavern owner brought in to work the tavern sex trade —women whose pay the tavern owner took. “He gets the drinks. That’s all he gets, and the customers we bring in, hijo de la chingada, sonofobitch.” My grandmother owned the value of her work, and she was not about to have it taken from her.

My grandmother and her fellow workers started a series of fights to smash up the taverns — to send chairs and tables flying, destroy alcohol inventory, and shatter mirrors. It wasn’t industrial sabotage on a grand scale, but it worked. They ran off the scabs and forced the tavern owners to back off so my grandmother and her sisters could make their own deals.

My grandmother considered herself a working woman. Her work fed her family. On busy nights, she sent her kids their dinner home in a cab; as a kid, Mother associated yellow cabs with chicken fried rice.

Grandma understood the importance of not selling herself short, of negotiating with the boss, and she insisted on solidarity among her sisters. In my organizing journey, I took what I learned from her and did my best to empower workers, share my skills, and build solidarity that would see us through the toughest battles.

One of my first experiences in an action was as a student at Roosevelt High School during the 1968 Chicano Blowouts in Los Angeles. In college, I was arrested as part of a multi-racial coalition of students who shut down the university administration building to protest cuts to the Educational Opportunity Program. Later, I cut my teeth as a community organizer against police misconduct in rural Oregon while becoming a rank-and-file leader of the National Organization of Legal Service Workers in Portland. After organizing and negotiating our first contract, I went to work for a number of unions, including AFSCME, SEIU, and CNA.

As a labor organizer who supported member-driven campaigns, I developed a blueprint for a fight, which I adapted from the Harvard academics Roger Fisher and William Ury’s book Getting to Yes. Mine was the “Homey D. Clown” version, “Getting to Yes or Kicking Your Ass.”

For example, while organizing a group of therapists trying to save a San Francisco community mental health clinic in the Outer Mission, I start by prodding the group to frame the problem as a question.

“So, what’s the question?” I ask the committee.

“The question? What do you think the question is? We’re dying here. No secretary, no email, down four therapists. What the fuck do you think the question is? The City is trying to starve us out.”

Framing the question, I tell them, will help us direct this fight.

“How can we provide the best services for our clients?” one member said.

“Great, frame the fight in the public good.”

Next key step: What’s the data? How can we document the impact of the city’s neglect on the elderly, poor, and mentally ill? How can we quantify it in real terms? Who has the power to get us what we want?

Data not immediately available gets tasked out. Who could get what? When can we get it? As the committee begins to collectively see what they have, they start to analyze the problem organically in their own terms. They get focused on their strengths and not where they’re stuck. They take ownership of the problem and move away from the, “You’re the union, you fix it” approach.

The butcher paper starts to fill up. I use the information to set up a parallel litigation track. Unfair labor practice charges are useless by themselves, but they can be useful propaganda tools to signal to the boss that we’re serious and know what we’re talking about. Any successful organizer will tell you that the real power is in organizing.

The third key step is brainstorming, prefaced by basic ground rules: no judging, no comments, and no evaluation. Everything goes up to see what sticks. Anything is allowed. Cut loose — wild, crazy ideas, whatever.

The butcher paper fills up with ideas; the discussion is instructive and lively. In this Freirean moment, the dialectic shifts and the “teacher” becomes the learner. The job here is to listen, probe, challenge, and tell stories — not to figure it out for them. The hardest and best thing to do is to wait. To let what’s organically theirs emerge. It can be hell for a fixer not to fix, for a rescuer not to rescue, for a know-it-all not to give the answer. Hellish though it may be, it is always worth the wait. When you get to that tipping point, it’s the best part of the work. The “students” start to lead, and ideas break through into possible actions.

Actions are organized, categorized, and evaluated against a standard of risk and involvement. The action must be SMART: Strategic, Measurable, Accessible, Relevant, & Timely.

The developing game plan on the wall — with a calendar — makes the campaign accountable and provides a way to measure progress, to adjust tactics as needed, to factor in new information, and to have a document for evaluation when the campaign is over. In larger campaigns, there is also a map that locates members by concentration and function. We meet weekly to carry out our campaign using the rest of the 10-step process.

This is where I break with Fisher and Ury, who go on to develop a method of consensus building with the boss. In my experience, there is no will to consensus without a recognition of power. I use a truncated version of their steps to build power first. Dealing with the boss is for later.

One group was so terrified of the boss they couldn’t agree on a slogan for a basic sticker campaign, so they decided to leave their stickers blank. The blank round sticker would symbolize their muted speech. Stickers were everywhere. They all wore them to the boss’s next mandatory meeting. It didn’t take long for that boss to cave.

Small actions are prized by The Art of War author, Chinese general Sun Tzu, as incremental engagement in the periphery, providing for the widest field of action with the enemy and an opportunity for the enemy to withdraw or change position. The following are examples of organic actions — each action, a different expression of worker activism.

· City of Portland Parking Deputies carried out a series of wildcat strikes to protest bad working conditions, take backs, and health care cuts. All day, cars parked in front of downtown department stores had red warning notices flapping on their windshields instead of parking tickets. No tickets — meaning nobody moved their cars. Retail revenue losses were huge. The Mayor, beholden to downtown businesses, was livid. The parking deputies not only interrupted the city’s cashflow; they hit the city’s business interests too. The city never knew when the next red warning day would be. Only Sabocat — the IWW symbol used to send a message to the bosses that an action was imminent — knew.

· Public defenders in Portland, Oregon, organized a strike that shut down the Multnomah County Courthouse. They struck over pay, caseloads, and racial injustice. Their slogans were, “The lawyers who put you in jail make 40% more than the lawyers who keep you out” and “The criminal justice system is rigged.” The DA paced in front of the shutdown courthouse. There would be no filing fees that day, no fines, and no miscarriages of justice. Lawyers, their clients, and the community stumped under a tree in a park across from the courthouse to bear witness and tell stories. There was a palpable joy in their defiance, the same joy I heard in my grandmother’s voice.

· City of Oakland parking deputies exposed a citywide two-tier ticketing system that gave warnings to the rich in the hills and tickets to the poor folks in the flatlands. The tactic worked because parking deputies tapped into the pervasive issue of double standards in Oakland, one for the rich in the hills and one for the flatlands where they lived and worked. Front-page coverage embarrassed the City of Oakland and launched an investigation into city ticketing practices. A key leader in that campaign was quoted as saying, “We service the community, and I don’t think we should take advantage of them.” Oakland parking officers told to enforce tickets selectively She spoke as a city worker as well as a union leader and community member.

When workers win in this way — where they determine the means of engagement with their bosses — they do what Frantz Fanon describes as breaking the unspoken agreement with their oppressor to be complicit in their own oppression. These campaigns changed the power relationship between members and their bosses. New leaders demanded and got respect, learned tools of sustained battle that didn’t depend on an organizer, challenged old leaders, and held the union accountable for any changes to their contracts.

Each campaign I’ve worked on has made me a better organizer. I left each campaign with the knowledge that I had been true to my class and to the rank-and-file leaders I had the privilege to work and grow with.

All those years ago on that snowy night in Utah, Grandma put her hand on my face and said, “Someday, mija, you’ll learn the difference between a whore and a working woman.” At seven, I couldn’t know the full scope of my grandmother’s work or what her words meant, but the power of her fighting spirit was undeniable. I later realized the full meaning of what she said: there’s a difference between a woman who sells out and one who stands her ground to fight the good fight, win or lose. She would never know the power that her words had on my life.